In winter and early spring, food sources along the Inside Passage are highly localized. In March, herring spawns. In vast schools the animals enter bays to deposit their eggs on kelp and eel grass. Humpback whales dive through clouds of fish, mouth agape. Above the water, gulls circle. Bald eagles wait in the trees above tidal narrows where currents pack the fish tight and push them towards the surface. In close succession, eagle after eagle swoops down, points his feet forward just before making contact with the water and clamps his talons around the writhing prey. There can be as many as several thousand eagles in a large bay. With competition high, many eagles devour their catch midair to avoid harassment by other birds and then dive down again to get seconds.

In early summer, Anan Creek is one of the best places in Alaska to view bald eagles. Hundreds perch in the tall Sitka spruce along the shoreline. At low tide, dozens sit on the mud flats in Anan Lagoon at the mouth of the creek. Generally bald eagles are spread out across the Panhandle during the warm months of the year. There are so many fish runs, so much salmon to be had, there is no reason to congregate on any specific stream. However, the Anan is an early productive run in the region and eagles flock in. By August, their lines have thinned again. Although salmon are still migrating strong up Anan Creek, there are other places where food is caught easily, and no reason remains to compete over the same resource.

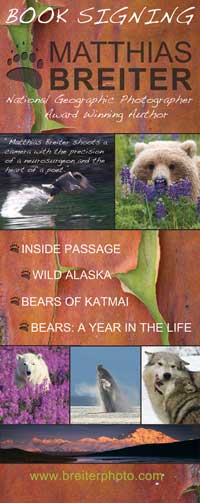

Taken from Matthias’s award-winning book Inside Passage.

It looks like one of nature’s follies that bears are born during the worst of winter. No other mammal living in the North gives birth at this time. And no other mammals except the

It looks like one of nature’s follies that bears are born during the worst of winter. No other mammal living in the North gives birth at this time. And no other mammals except the